On the way back to Dallas today, we made a stop in Baird. We've been here once before and here is the LINK to previous stop. Today, we are hoping to revisit Primal Brewing, but it is no longer here. Well, how about a stop at the visitor center. It wasn't open during our last visit and learning more about the small towns in Texas is fun for both of us. The visitor center is located in the old Texas and Pacific Railway Depot. The Texas and Pacific Railway arrived here in 1880, platting a town near the work camp of Matthew Baird, surveyor and engineer. In 1881, the T&P built a roundhouse and immigrant house, and moved a depot building to this new railroad division point. The town of Baird prospered and became county seat in 1883. A frame depot built in 1905 converted to storage when replaced by this two-story brick depot in 1911. The prairie style building features a decorative belt course, overhanging eaves, low-pitched roof, and unusual Flemish style parapet. In 1977, the railroad discontinued use of the building, which still recalls the town's importance as a shipping point. Pictured below is the view from the depot. Courthouse at the other end.

Inside the depot is a small museum. Take a peek around. We are told that each building in the town had one of these inside.

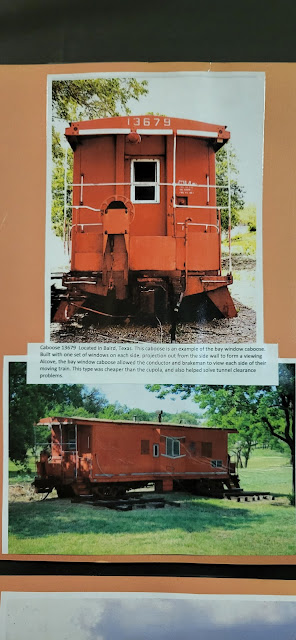

"Following World War I, the all-steel construction of cabooses began. The newly constructed cabooses had steel center-sills and underframes. This advanced caboose design better protected the rear end crew against the train's slack action. By the late 1920's, newly constructed freight cars were taller than most cupolas. The prompted the invention of the bay window caboose. Built with one set of windows on each side, projection out from the side wall to form a viewing alcove, the bay window caboose allowed the conductor and brakeman to view each side of their moving train. This type was cheaper than the cupola, and also helped solve tunnel clearance problems faced by many eastern railroads. Railroaders affectionately called their caboose by many nicknames, including cabin, crummy, buggy, doghouse, waycar, shack, and hack. Most railroads painted their cabooses 'boxcar red' for high visibility. However, after World War II, the 'little red caboose' shoed up in many different colors, typically associated with the paint schemes found on the railroads' new diesel locomotives. Cabooses were expensive to build and maintain, unlike regular freight cars, which earned their keep. Extra switching moves were needed to add or uncouple a caboose at the end of a train, and they required caboose tracks at major yards, as well as Carmen and laborers to work on them and service them. In 1980, the cost of operating a caboose was 92 cents per mile. As railroad technology advanced, the caboose's function became less important. The introduction of remote switches thrown by dispatchers at CTC consoles meant a rear brakeman wasn't needed to close behind a train. Many railroaders believe the final nail in the caboose's coffin was the 'End-of-the-Train' telemetry device. This small box fit over the rear coupler of the last car on the train, and connected to the train's air brake line. It sent a periodic signal to the locomotive indicating the brake pressure at the rear of the train, whether or not the last car of the train is moving, and in which direction. The caboose cost about $480,000 - more than the cost of most freight cars - and weighs about 25 tons. It can be replaced with a box that costs about $4,000 and weighed 35 pounds. One by one throughout the 1980's, individual states repealed age-old laws that required the use of cabooses in train operations. The last state to do so was Virginia, when it relented on July 1, 1988. In the mid 1920's there were approximately 34,000 cabooses operating on U.S. railroads. Today, only a few hundred cabooses remain, used in transfer work, and on yard jobs, work trains, and trains that require backup moves. The colorful caboose that generations once looked for at the end of every freight train is now a thing of the past, replaced by modern technology.'

No comments:

Post a Comment